Alberto Zerain and Mariano Galvan’s Nanga Parbat Rescue. The “Boots On The Ground” Report of How Things Unfolded

by Alex Găvan, co-initiator, coordinator of the technical part of the rescue and helicopter searcher of Alberto Zerain and Mariano Galvan on the Mazeno Ridge of Nanga Parbat-8125m, between June 26th to July 1st 2017

I so much longed to stand atop the 8125 m summit of Nanga Parbat. I so much dreamed about this magic mountain and hoped to make it my seventh eight-thousander climbed without the use of supplemental oxygen or hiring high altitude porters. So here I am, on this knife-sharp ridge, 6000m high almost, living the dream. Because the very fabric of life is action, not only plain dreaming. The place is so narrow that only three tents have been set up here, each on successive higher platforms, and this only after much work have been done by shovelling the frozen snow to create a livable habitat. The place feels like being out of this world. Between the sky and the earth, it is our safe place in this endless, 4 km high world of ice and rock. Nanga Parbat, this huge, vertical ladder of Jacob, connecting us to the higher realms within ourselves but ceaselessly challenging our humanity with every step, with every breath. Below us, on each side, a hypnotizing and vertigo like void is voicing expectations, hopes but also fears and warnings.

Climbing to Camp 2 on the Kinshofer route on Nanga Parbat the day I received the last SMS from Alberto Zerain. Climber in the image is Benjamin Grueber, June 23rd 2017 | photo Alex Gavan

Climbing to Camp 2 on the Kinshofer route on Nanga Parbat the day I received the last SMS from Alberto Zerain. Climber in the image is Benjamin Grueber, June 23rd 2017 | photo Alex Gavan

It's the afternoon of June 23rd. For the last eleven hours I have been climbing together with Italians Klaus Gruber and Benjamin Grueber of South Tyrol, ferrying big loads from Camp 1 to Camp 2 and in the meantime furthering our acclimation process. I feel dead tired; my body is aching. We’re doing the Kinshofer route and I love each and every moment of being here.

Camp 2 at almost 6000m on the Kinshofer route of Nanga-Parbat, the day and the place where I last had a sign from Alberto;Klaus Gruber and Benjamin Grueber in the image, June 23rd 2017 | photo Alex Gavan

Camp 2 at almost 6000m on the Kinshofer route of Nanga-Parbat, the day and the place where I last had a sign from Alberto;Klaus Gruber and Benjamin Grueber in the image, June 23rd 2017 | photo Alex Gavan

I open the satellite phone to announce my support team in Romania I’m fine. One particular SMS is popping up and gets my attention: “Hi Alex, we are fine at 6000m. Tomorrow we are going to the Mazeno Peak. And descent later from the coll to the Base Camp”. It’s Alberto Zerain, the accomplished Spanish climber from the Basque Country. Together with his rope partner, Mariano Galvan of Argentina, they are climbing the infamous 13 km long Mazeno Ridge, the lengthiest arête on any 8000m peak. A truly stellar team. Despite many attempts this route has been previously climbed only once, back in 2012. And despite using high altitude porters’ support, the team of Sandy Allan and Rick Allen has received “Piolet d’Or” for it, the highest distinction in climbing, the equivalent of an Oscar Award. Down on the glacier I am sharing the Base Camp with Alberto and Mariano and while we are on the mountain I am also sharing with them my weather reports. “Hi Alberto, all good? My forecast says it snows till next Friday. I am in Base Camp now, slept in Camp 2 last night. Best and stay safe”, was the message I sent them the next day, on the 24th. For this last message I did not get a delivery confirmation like I usually do, but I didn’t worry since I got used with often satellite network’s errors.

--with-Alberto-and-Mariano-on-our-approach-trek-to-the-Base-Camp%2C-14-June-2017%2C-foto-Alex-Gavan.jpg) Last photo I took (with my smartphone) of Alberto and Mariano. It is from our approach trek to the Base Camp, June 14th 2017 | photo Alex Gavan

Last photo I took (with my smartphone) of Alberto and Mariano. It is from our approach trek to the Base Camp, June 14th 2017 | photo Alex Gavan

Nevertheless, in the evening of Monday June 26th I was discussing over dinner their lack of communication with Abdul Ghani, our cook assistant and also a longtime friend of Alberto. They left for their climb on the 19th, with food for seven days and now there were already eight days since then and four days since my last contact with them. We concluded that the next morning I shall call Anwar Syed, the owner of Lela Peak Expeditions and the man who logistically organised our expedition till the Base Camp. We shall launch a helicopter search mission for our friends the soonest the weather will allow. Yet Anwar seemed to have similar ideas with ours. He called later that night asking me what I believe about doing a heli search for the two climbers up the Mazeno. The wife of Alberto called him short after she started worrying of losing the contact with him.

That same night I got in contact with Patricia. For almost one hour, we were discussing all the possible variants and sharing with her the experience of my seventh previous helicopter rescue missions I either organised or I had been part of in the Himalayas during the years. This was besides the rescue operation of Inaki Ochoa on Annapurna in 2008, in which my role was a minor one due to my physical and health condition at the time for I was just down from a 8463 m climb to the top of Makalu. Yes, we needed to organise a searching flight. This is how all started.

But here is not Europe, here is Pakistan, and there are certain and precise steps to be made when organizing such an undertaking. There is only one company to do it, a monopoly, the military controlled Askari Aviation. And even if you have one of the best rescue insurance policies in the world, like I do (mine is done with the Global Rescue and it gets me covered up USD 500 000), you still have to deposit in advance via bank transfer 15,000 USD, money that you will get back, minus a service fee, if nothing bad happens. They got duped in the past by insurance companies or by people not getting them paid and now they will simply not fly otherwise. At the same time, it is their policy that a mission of such a magnitude needs and must be sustained by two helicopters flying in tandem.

It came out that Alberto’s insurance was coming along by default with his membership at “Federation Francaise des Clubs Alpins et de la Montagne”. A 30,000 euro coverage from AXA. And while this amount was good enough for a climbing trip in the European Alps, where most of the times a rescue helicopter is just five minutes away, it certainly was not up to the task in the Himalayas. Here, each intervention starts from dozens of thousands of euros up. One helicopter rescue operation I organised years ago in the Nepal Himalayas had a cost of 80,000 euro. The guy survived but he was not insured and he had to pay it all from his own pocket. During the days of the search, Anwar Syed contacted Global Rescue. Later on, Ivan Ivanissevich, the Ambassador of Argentina in Pakistan contacted the American rescue company. On both occasions, Global Rescue stated that Mariano Galvan is not showing up in their database as a their customer.

Because this financial detail had to somehow be sorted out, even though the weather was good for flying on the 27th in the morning, the helicopter didn’t fly. The whole day had been spent between Alberto’s support team in Spain and the Spanish embassy in Islamabad in order to sort out the situation and find a working money solution to the insurance issue. In the end two option remained on the table: either the money to be deposited in the Askari bank account or, the embassy was to release towards Askari a payment guarantee letter. The first option was impossible to fulfill because the bank transfer of the money from Spain would take several days to arrive in Pakistan. Also, Anwar Syed himself offered to give his own money and make the deposit in the name of the climbers but being just after the Ramadan, all the banks were closed. Finally, Wednesday, at around 1,30am, Pakistan time, Alberto’s team from Spain sent the email requesting the Spanish embassy to release the guarantee letter towards Askari. At around 2am, the embassy did so. During the whole day on 27th I repeatedly asked people in Spain and also Anwar Syed to make sure with the embassy and Askari Aviation that, if the weather is fine, the helicopter shall come in the very morning, or the weather might change as it usually did the previous days and therefore become impossible for flying safely. In parallel I received from them the latitude and longitude coordinates of the climbers’ last known position. I made a thoughtful searching plan, prepared a long line system for the helicopter, had my altitudes medicines ready, survival blankets, as well as emergency supplemental oxygen, some drinks and a little bit of food, just in case. I had to borrow a harness and a pair of crampons from a Sherpa of a commercial expedition since my gear was up Nanga Parbat, in Camp 1.

On Wednesday the 28th, Anwar was asked to be on the helipad at 7,30am for the helicopter take off scheduled at 8am. The helicopter flew from the military air base in Skardu at 8.49 am. So hopelessly late since I so much insisted that they make sure the flight will arrive in due time. By the time it landed into the Nanga Parbat Diamir Base Camp to pick me up, clouds on the Mazeno already started to show up. We went on to retrace climber’s steps since Alberto, in a previous discussion, also showed me the exact entrance on their proposed route. Our main target was to reach their last recorded GPS position and, if needed, to expand our search starting from that point on.

Alex Gavan during the first heli rescue flight, June 28th 2017 | photo Alex Gavan Archive

Alex Gavan during the first heli rescue flight, June 28th 2017 | photo Alex Gavan Archive

We found their tracks. They were clearly visible on the mountain and we closely followed them along the sharp ridge. We came short of reaching their last GPS point but had to abort flying over that area since the clouds made it much too dangerous to continue. To use the resources effectively, we turned out our search on the Diamir side of the Mazeno where the meteo conditions allowed us to have an in-depth check of the whole length of the ridge.

Unknown to me at the time, the people back in Spain had the whole overview of the climbers’ route. Strangely enough, this vital piece of information has not reached me at any point, though I repeatedly asked for additional information I felt like they knew it from the Racetracker device log. I had absolutely no other info than their last known recorded position.

For the next two days, on 29th and 30th of June, the falling snow and other bad weather conditions in Nanga Parbat did not allow another helicopter flight but in the meantime I realised that if a proper rescue is going to be done then I have to take the matter further in my own hands. Therefore I managed to get in contact directly with Major Abid, the pilot I flew with on June 28th. The agreement with Askari Aviation and with Major Mazhar at the Skardu Air Base was that I was going to wake up every morning at 4 o’clock, check out the weather and if I consider there are good flight conditions, then I will directly call Abid to give him the green light. Everything was visual, they could not navigate their way through the mountains otherwise. For all these days the two helicopters stayed in stand by for the rescue at a nearby helipad, thirty minutes away from the basecamp.

Three rescuers from the Pakistani public emergency service of 1122 arrived in basecamp on June 29th from Chilas. Since it would have been impossible for them to reach the climbers’ last GPS position and still if they further tried they would have greatly endangered their lives, I simply had no choice but sending them back together with a letter of gratitude towards their superior.

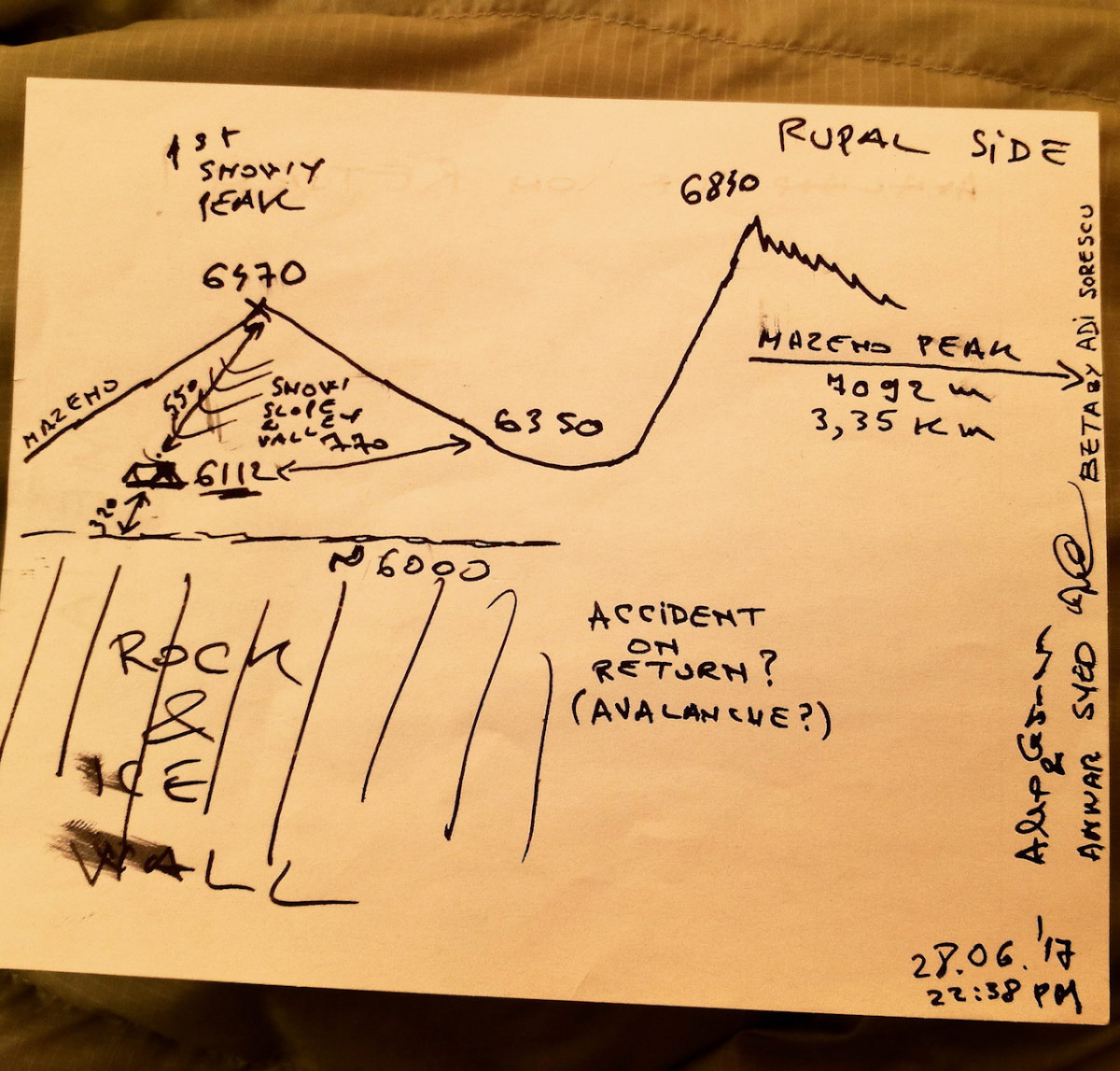

I also had a phone call with Adrian Sorescu in Romania about matching on Google Earth the coordinates I was given from Spain, in order to create a logical story out of the otherwise dull numbers given by latitude and longitude. As I expected, the place of the last GPS known position turned out to be on the Rupal side of the Mazeno Ridge. In an hour long conversation over satellite phone (nobody in the basecamp had internet access), as well as with the help of Anwar, I managed to get myself a pretty clear picture of what I believed had happened.

My drawing of what happened made after a discussion over satellite phone with Adrian Sorescu in Romania, June 28th 2017 | photo Alex Gavan

My drawing of what happened made after a discussion over satellite phone with Adrian Sorescu in Romania, June 28th 2017 | photo Alex Gavan

On June 27th, one Spanish journalist called me up but all I could confirm was that I indeed managed the rescue from the base camp but while the rescue is ongoing would not be ethical on my part to comment any further. The same journalist called again after the first flight and again I did not comment, but I told him there is actually one thing he can do: to call the Spanish embassy in Islamabad and pressure them to make all efforts that the heli will not again be late next time. I did the same on phone conversations with the ambassadors of Spain and Argentina. They repeatedly sent official letters to Askari Aviation on 28th, 29th and 30th of June, stating the importance of and asking them for the helicopter to arrive in time. Those were quite tense times. The money matter was still not yet fully resolved. Only the first flight cost was 19,090 USD out of those 30,000 euro covered by the insurance. I even discussed with Anwar the possibility of calling my own sponsors in Romania to help in his matter if no other option will show up in real time.

Because time was now the critical factor in what we thought to be our friends’ survival. According to the statistics those people were dead. But then there are also some real life stories of miraculous Himalayan survival defying and challenging those very same statistics. As long as we did not have clear and concrete evidence of the climbers’ peril, it was our duty to continue the search.

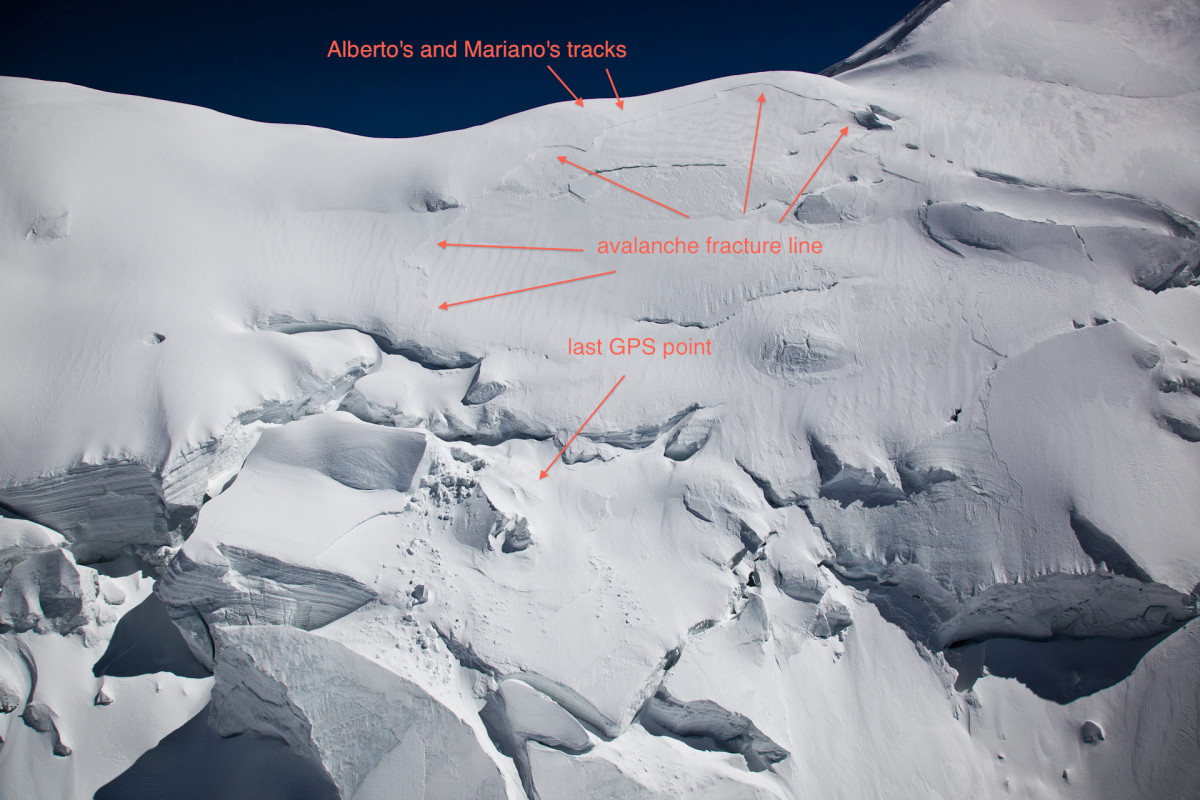

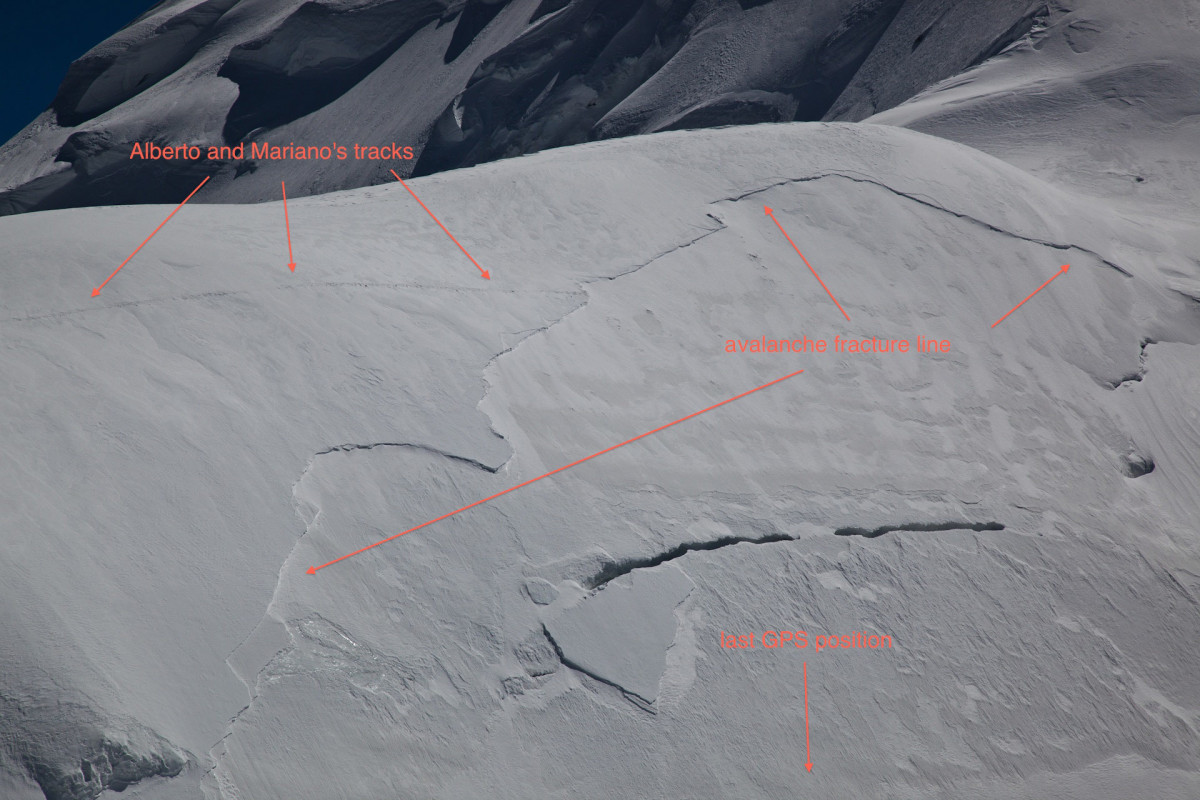

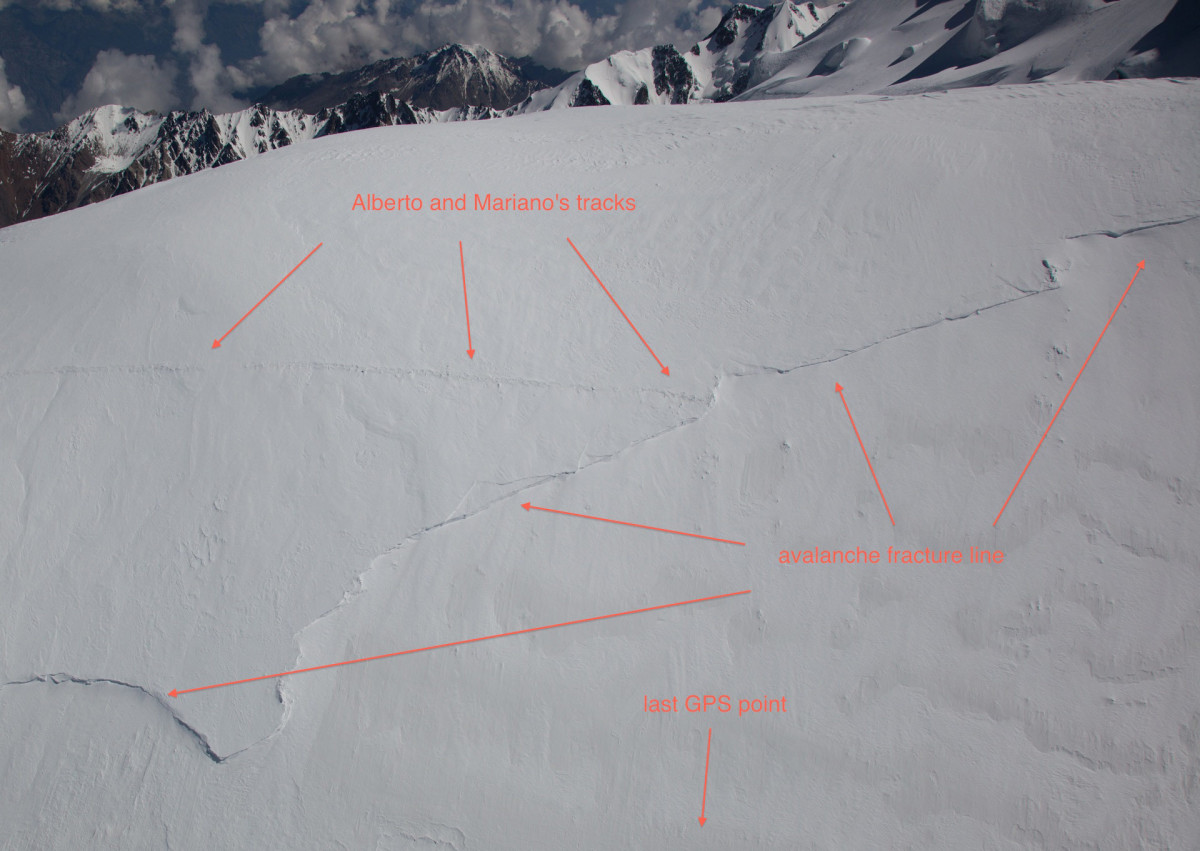

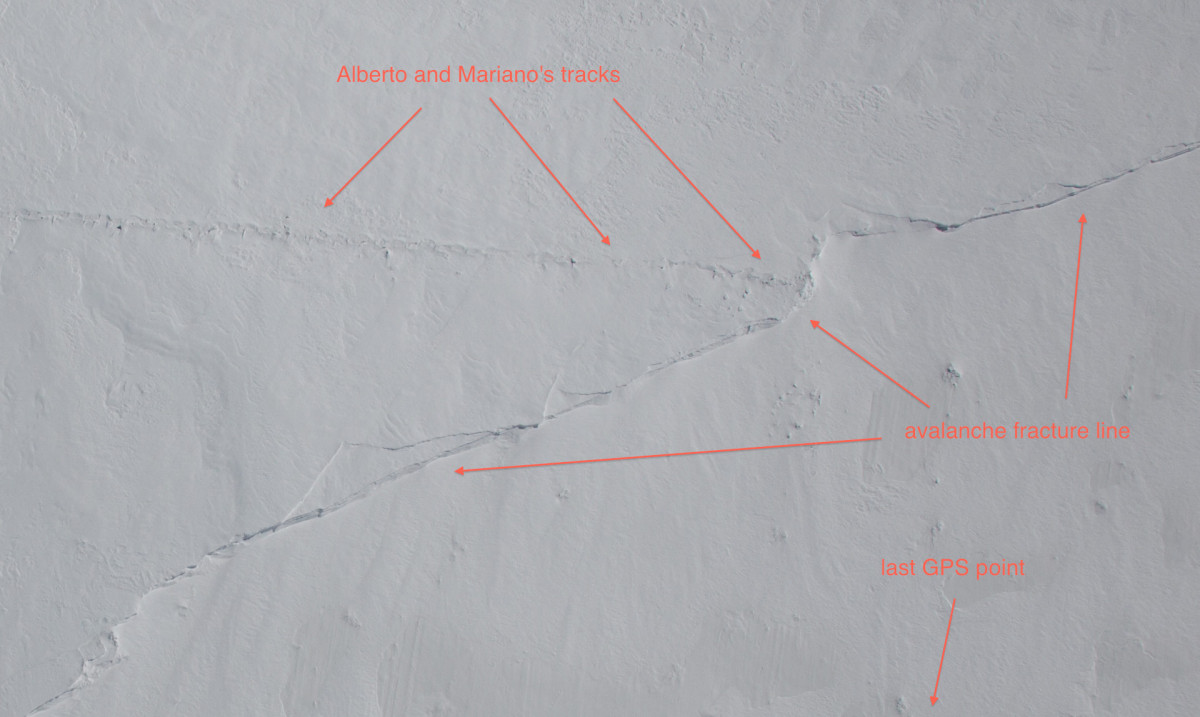

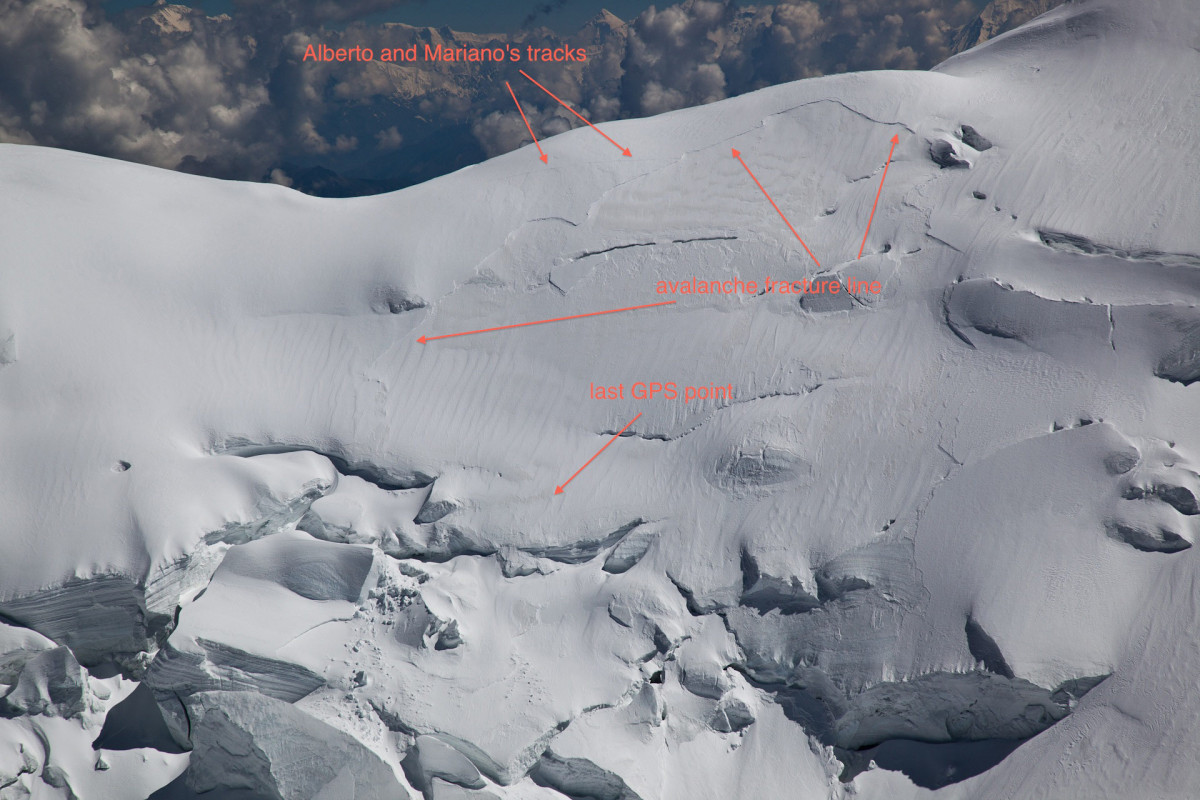

Finally, on July 1st, the weather was crystal clear and I was picked up by the helicopter from the basecamp at 6 o’clock sharp. We soon reached the given GPS point and saw on that place precisely significant evidence of a massive slab avalanche: the fracture line, much debris and more disturbing, Alberto and Mariano’s tracks abruptly ending on one part of the fracture line and not showing up again in any other place. Other than this, absolutely nothing to be seen out of them.

Alberto Zerain and Mariano Galvan's tracks on the Mazeno Ridge, Nanga Parbat 8125m, July 1st 2017 | photo Alex Gavan

Alberto Zerain and Mariano Galvan's tracks on the Mazeno Ridge, Nanga Parbat 8125m, July 1st 2017 | photo Alex Gavan

Alberto Zerain and Mariano Galvan's tracks on the Mazeno Ridge, Nanga Parbat 8125m, July 1st 2017 | photo Alex Gavan

Alberto Zerain and Mariano Galvan's tracks on the Mazeno Ridge, Nanga Parbat 8125m, July 1st 2017 | photo Alex Gavan

Alberto Zerain and Mariano Galvan's accident place on the Mazeno Ridge, Nanga Parbat 8125m, July 1st, 2017 | photo Alex Gavan

Alberto Zerain and Mariano Galvan's accident place on the Mazeno Ridge, Nanga Parbat 8125m, July 1st, 2017 | photo Alex Gavan

Alberto Zerain and Mariano Galvan's tracks and the avalanche fracture line on the Mazeno Ridge, Nanga Parbat 8125m, July 1st 2017 | photo Alex Gavan

Alberto Zerain and Mariano Galvan's tracks and the avalanche fracture line on the Mazeno Ridge, Nanga Parbat 8125m, July 1st 2017 | photo Alex Gavan

Alberto Zerain and Mariano Galvan's last tracks and avalanche fracture line on Mazeno Ridge, Nanga Parbat 8125m, July 1st 2017 | photo Alex Gavan

Alberto Zerain and Mariano Galvan's last tracks and avalanche fracture line on Mazeno Ridge, Nanga Parbat 8125m, July 1st 2017 | photo Alex Gavan

Alberto Zerain and Mariano Galvan's last tracks before the avalanche on Mazeno Ridge, Nanga Parbat 8125m, July 1st 2017 | photo Alex Gavan

Alberto Zerain and Mariano Galvan's last tracks before the avalanche on Mazeno Ridge, Nanga Parbat 8125m, July 1st 2017 | photo Alex Gavan

We went back to refuel and in the meantime I consulted with Alberto’s wife and decided for one more search flight. Also, in a pretty heated conversation in Spain I found out more information in five minutes than in all those days when I was continuously asking for more information. According to the Racetracker device, Alberto and Marino went just uphill the Mazeno, had no return tracks showing the intention of an early retreat from the climb, seemed they never reached the Mazeno Peak (on the contrary they were pretty far from doing that) and on their last known position the GPS emitted signal from the same spot for more than ten hours before it stopped. In my mind everything got clearer and clearer.

Alberto Zerain and Mariano Galvan's avalanche place on Mazeno Ridge, Nanga Parbat 8125m, July 1st 2017 | photo Alex Gavan

Alberto Zerain and Mariano Galvan's avalanche place on Mazeno Ridge, Nanga Parbat 8125m, July 1st 2017 | photo Alex Gavan

Alberto Zerain and Mariano Galvan's general accident image area, Nanga Parbat 8125m, July 1st 2017 | photo Alex Gavan

Alberto Zerain and Mariano Galvan's general accident image area, Nanga Parbat 8125m, July 1st 2017 | photo Alex Gavan

We extensively again searched this area, looked up the open crevasses, searched the nearby valleys, searched the Mazeno up to almost 7400m, much farther than they could have realistically climb. The heli has one watch and when the indicator is on the red line the heli is going to crash. For parts of the flight, we were flying on the yellow line that is just under the red one, the impossible line. That far we went in our search. The pilots Abid and Azar, together with their copilots were truly amazing professionals. It was not just another job for them, I felt them really engaged in finding Alberto and Mariano. They went wherever I suggested them to and at the same time the coming up with their own well useful new ideas. Still nothing.

The evidence found on the climbers’ last known GPS point was much too heavy, much too hard to digest. But now everything was clear. It all finished back on June 24th but we could not have known this until now when we had the evidence. We flew a total of 6.5 hours of effective search, divided between the two helicopters, never both in the same time searching the same area. We double and even triple checked every square centimetre of the mountain. Still nothing.

Alberto and Mariano were among the greats.

Life is a gift. And those two amazing human beings did know how to cherish this gift by always looking for the good light.

Alberto Zerain, Mariano Galvan, Alex Gavan and Oscar Cadiach in Islamabad, June 12th 2017 | photo Alex Gavan Archive

Alberto Zerain, Mariano Galvan, Alex Gavan and Oscar Cadiach in Islamabad, June 12th 2017 | photo Alex Gavan Archive

Mountain is mountain and His sovereignty is absolute.

***

PS: in the aftermath of the Mazeno rescue I decided to cancel my current Nanga Parbat climb on the Kinshofer route.